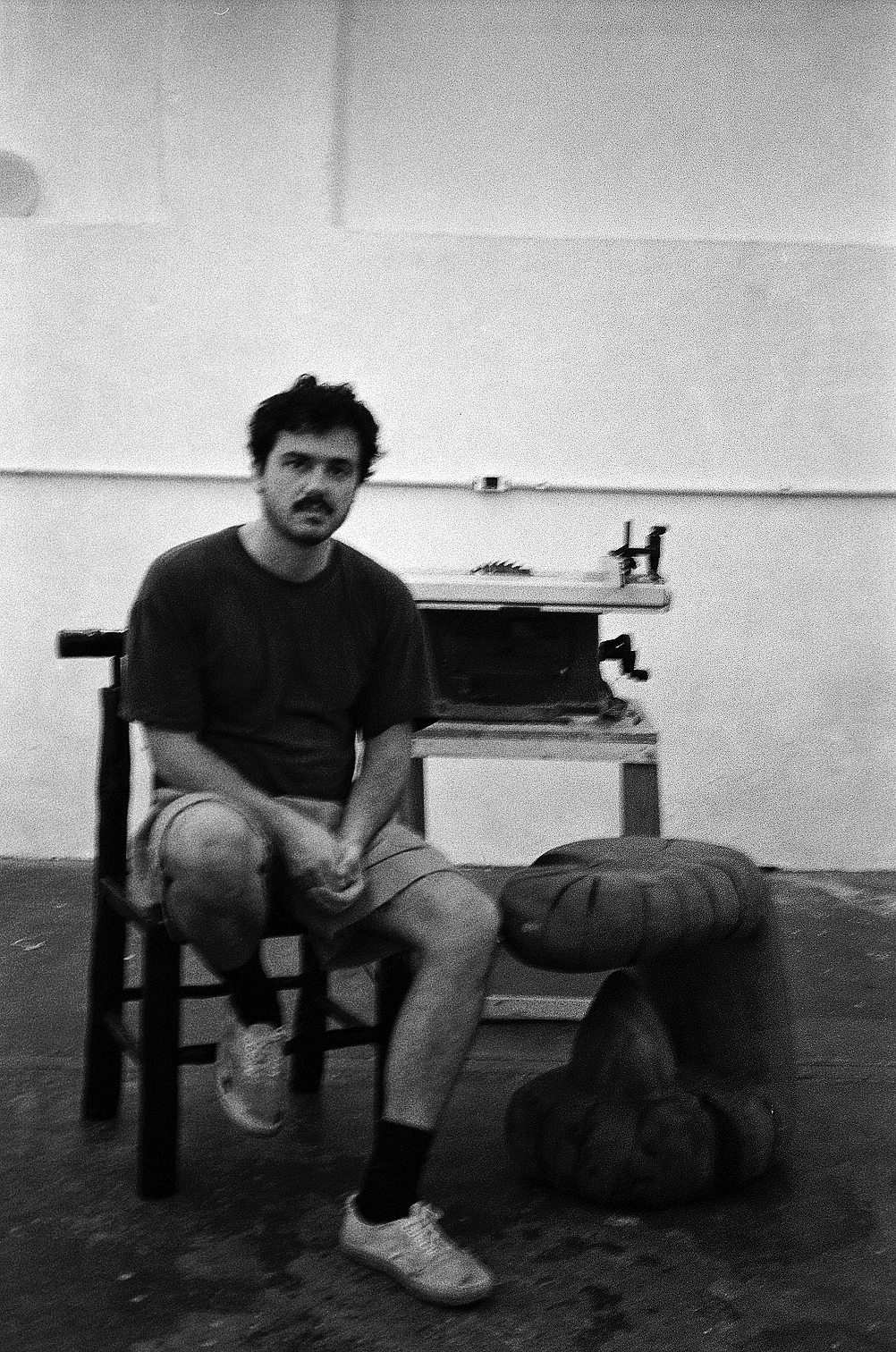

Text by Guilherme Teixeira

Photographed by Victoria Yamagata

–

How your belly fold as you sit, the memory of a father’s lap, the round shape. The creations of Pedro Avila [São Paulo, Brazil, 1988] arise from free-form sketches devoid of censorship. With the human body and its natural and organic shapes as a primary interest, the pieces from the series pi and cavas produce in our guts a slight feeling of discomfort that we somehow cannot name, yet we recognize the roots of it. Taking distance from an industrial, market- oriented background, Pedro denies the linear, lean surface, the plain plates, the tubes, and the rebars to inhabit a place where the ideal body does not follow any standard whatsoever but that which this standard denies and shame.

The ideal figure here is not modern or contemporary as it looks back to art history – from pre-Colombian and Paleolithic, aligning the idea of other possible bodies to how we conceive shapes and our environment today. Although we can see examples, throughout the twentieth century, of other possible bodies represented in works such as the ones from Julio Guerra [Brazil, 1912], such as the public sculpture Mãe Preta (Black mom), where it’s depicted a black woman breastfeeding a baby, the critical approach to them has always been through the perspective of a “grotesque proportion,” mainly when it depicted racialized and native communities.

The ideal figure here is not modern or contemporary as it looks back to art history – from pre-Colombian and Paleolithic, aligning the idea of other possible bodies to how we conceive shapes and our environment today. Although we can see examples, throughout the twentieth century, of other possible bodies represented in works such as the ones from Julio Guerra [Brazil, 1912], such as the public sculpture Mãe Preta (Black mom), where it’s depicted a black woman breastfeeding a baby, the critical approach to them has always been through the perspective of a “grotesque proportion,” mainly when it depicted racialized and native communities.

Operating a radically different system to this colonial and violent idea, Avila’s shapes detach the human body from this gaze, acknowledging its potential fully. It is as if pieces, crops, of full images take form and space as we face Veras Coffee Table and Dobra Side Table; its curves reveal themselves through the hardness of basalt or the transparency of fiberglass.

However these shapes and protuberances do not nod solely to the human body but also to how this body handles and works matter itself, as seen in the creation of Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino [Italy, 1942], whose practice on both clay and bronze evokes familiar shapes that exist as one with the environment, as seen on the work presented at the DOCUMENTA [2012] while also creating discomfort and doubt, as in the series Halimorphs [2016].

This duality, where the perception of shelter and distance operates hand in hand regardless of any contradiction, is also a core element in Avila’s practice, as we can see in pieces such as the Colo Lounge Chair, where the memory of sitting on a parent’s lap as a child proposes an object that, in its materiality, is both welcoming as it is threatening. Both denied and allowed in these pieces, the function is one of the many aspects of contemporary design that Avila’s practice questions, alongside its logic of production and the possibilities and responsibilities of it towards the future (and the past), with the environment’s and our bodies’ natural expressions as its motive.